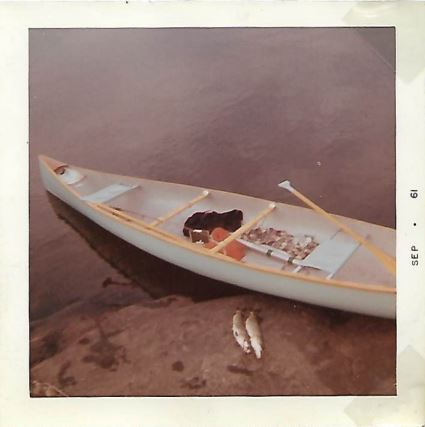

I made up the recipe for fish chowder while on a canoe trip to the wilderness area near the border of Manitoba and Ontario in 1961. I still use essentially the same recipe today.

This story began when I decided to take a sabbatical from Cornell after my freshman year to hitchhike around the US and grow up. After hitching to Miami, I got a job as a deckhand on the Brigantine Yankee, where I spent nearly six months sailing around the Bahamas for Windjammer Cruises. There I met Jack Alexander, a passenger from Minnesota. I guided him on a couple of SCUBA dives and towed him back to the ship with his tank empty and sharks circling.

I had the 4 to 8 watches, morning and evening, with the Captain because the Skipper was teaching me celestial navigation. At about 7 am, he would go below to clean up for breakfast with the guests. Before that, I would run forward to the galley to get a cup of coffee. Nobody could cross the threshold of Frank’s galley except for the Captain and me. I was Frank’s pal because I’d bring him a nice grouper now and then so he could make his chowder, and gig enough lobsters to feed everybody on board when we anchored off Great Isaac’s Lighthouse.

Jack Alexander rose early and, after being rebuffed by Frank (perpetually cranky), talked me into getting him a cup of coffee. We did a lot of talking while I had the wheel.

After five months I had to regrettably leave the Yankee because I needed money to go back to Cornell. I had just turned 19 while aboard and returned to hitchhiking, this time to the West coast. I traveled with Rip Bliss, a fellow crewman from Yankee. We first hitched to Chicago so we could go the entire length of Route 66. This adventure is covered extensively in the blog post, “Hitching”.

Once we finally made it to Los Angles, we turned north, and on May 1st, arrived in Seattle. I was pretty much out of cash and Rip completely out. We needed jobs and quickly. After being rejected by the Smoke Jumpers, we hooked up with the Forest Service Pine Shoot moth survey. We traveled around western Washington driving through neighborhoods looking for the moths in garden shrubs. It was a blessing as we were on per diem and therefore had food and lodging covered. That ended when I got sent back to the headquarters to take over the office and rearing of the samples we collected. We raised the samples so we could identify the adults. I had taken a semester of entomology so I was the most qualified. Ha!

The HQ was an abandoned lumber warehouse, so no bed, no fridge, and no stove. With a hot plate, a few pans I bought in a Seattle hock shop, and by running cold water slowly in the bathroom sink overflow, I had the food situation covered. I slept on a half couch with my feet on a folding chair and covered myself with a Marine blanket from my duffle bag. It sucked.

About two weeks of that routine, a letter from Jack Alexander arrived. He wanted me to call him about a job in Minnesota. So I called and Jack explained he wanted me to play big brother to his two boys while living at a cottage on a lake. I was suspicious. It sounded too good, so I was hesitant to commit. I was only 19 but had seen enough to be suspicious. He said that he would send me a plane ticket to come and look it over and a return ticket. If I decided to take the job, I would fly back with my gear after giving my notice to the Forestry Service.

I had only been on two airplanes in my young life, both courtesy of the US Navy. I flew to Pensacola Naval Air Station during spring break of my freshman year. They were trying to convince young NROTC students to sign up for pilot training after graduation. I had no intention of being a pilot but I enjoyed eating, and since the fraternity house where I worked for my food would be closed, my food source was gone. I knew the Navy would feed me three squares a day, so I went.

The Carevelle jet flight from Seattle to Minneapolis was nothing like the Navy DC-3 and T33 trainer. Champagne and steak!

I got to meet the boys–John, 13 and David, 9–and see the situation first hand. Jack visited that evening he explained that as VP of Sales for the granite company he was absent much of the time. His wife was a wheelchair bound MS victim and he did not want to leave the boys alone all summer. Jack’s cabin was under construction, so I stayed at his Dad’s cabin (also named John) directly across Big Fish Lake.

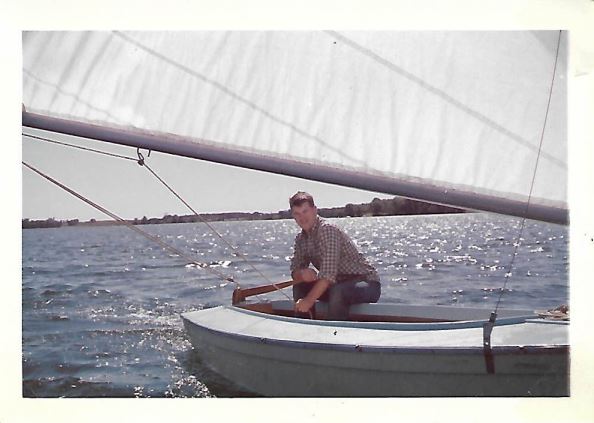

My job was to spend time with the boys and teach them swimming, sailing and anything else I could think of, while getting a nominal hourly wage for working at John’s place cutting brush, chopping wood, and other odd jobs. Jack would supplement my pay at the end of the year sufficiently to return to Cornell. I would still need to work for my food, and likely get some scholarships and loans to pull it together, but it was such a good deal I could hardly refuse.

So I returned and set up housekeeping in John’s cottage. We had swim lessons, some gymnastics and fishing. We built a dock and a float, and I climbed a huge tree and we hung a thick rope from it to make a rope swing. During working hours, we continued work on John Senior’s acreage of woods across the lake.

We noticed a pair of hawks building a nest up high in a very tall tree and thought I’d try to capture one of the chicks just before it learned how to fly.

Jack bought a small sailboat and a number of others on the lake did likewise. I had to rig most of them since they came disassembled and no one else seemed to know much about it. I started teaching people how to sail.

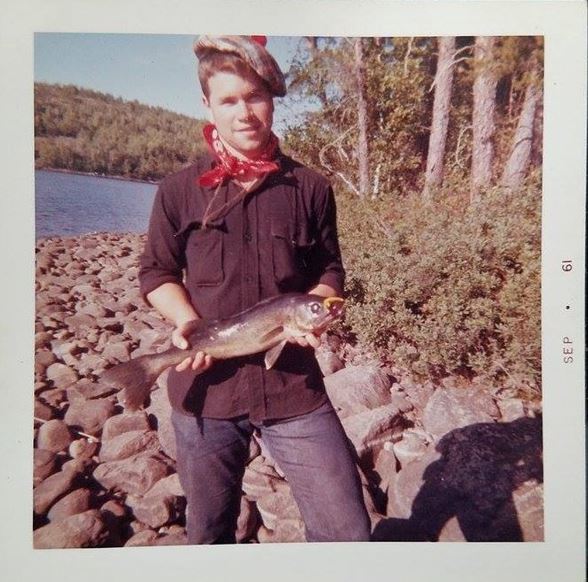

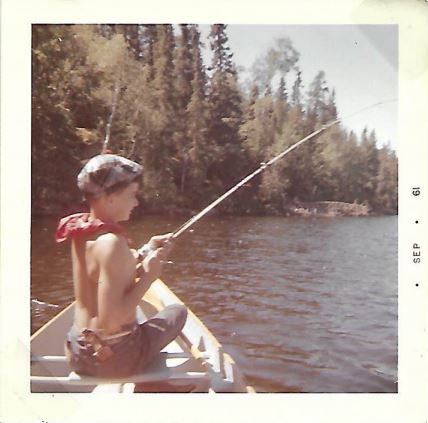

During the first week of June we took a canoe trip to the wild area north of Lake Superior and outfitted with Gun Flint Lodge.

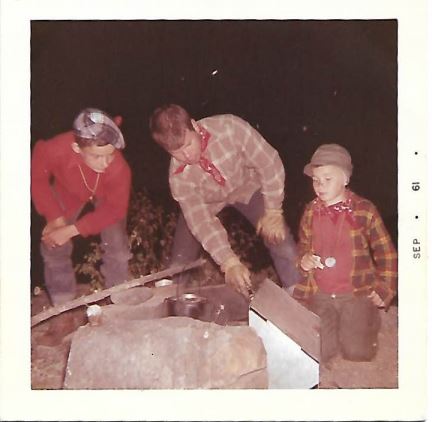

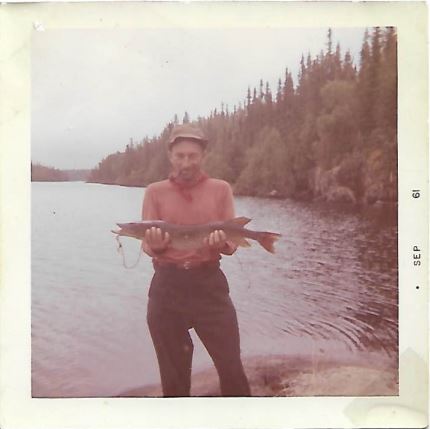

There were 8 of us in three canoes: Jack, John, and Dave and Zeke Zenner and his three boys, Guy, Mark, and Dain. The campsites were already established as this was a common canoe trip route. Nonetheless, it was rugged enough for the young kids. The fishing was fantastic! We caught pike, lake trout, small mouth bass and plenty of big walleyes. Jack landed the biggest walleye I had ever seen before or since, weighing in at 12 to 13 lbs but there were a number of others in the 4 to 7 lb class.

At the conclusion of that trip, Jack asked if John and I would like to stay another few days. Answer, Yes. We resupplied and headed out for exploring some different and off the beaten path lakes. We fished Ogiskemunche, Jasper, Kingfisher and Rice. The portage into Rice was so overgrown that I had to force the canoe I had on my shoulders through the brush and collect swarms of mosquitos under the canoe. We caught some rainbows in there and bass, walleyes and lake trout in the other lakes.

By the time we got back the baby hawks were nearing the day that they would leave the nest so we decided it was time. We knew that mama and papa hawk were not going to be thrilled with me swiping one of their chicks so I bundled up with a canvas rain jacket with towels across my shoulders underneath. I wore a hard hat held in place by the hood of the rain jacket. The climb up the tree would be tricky because for the first 35 feet or so there were no branches and the tree was pretty thick. Fortunately, I never gave much thought to falling. The hawk parents were repeatedly dive bombing me and screeching although they never actually hit me. I grabbed a chick and dropped him into the bushes below. He spread his wings to break his fall and he survived.

We put him on a perch we had built out in the yard and started to feed him chipmunks. As he grew and the chipmunk population declined we switched to stew beef. We knew little about training a hawk but constructed a lure that we would swing around and reward him when he attacked it. Since he was not restrained to the perch he eventually flew up into the surrounding trees and the training program stalled.

We had other things to think about as we started planning a trip in August to an area outside of Lac Du Bonnet, Manitoba, located about 90 miles north of Winnipeg. Cold Spring Granite had a quarry and factory there. Jack ordered two fiberglass canoes and had them shipped to the plant. (We’d used aluminum canoes at Gun Flint and they were too noisy.)

As the weeks passed, we got more serious about planning for the trip. First, we got maps and aerial photos of the area where we planned to go. The photos we laminated in plastic with a piece of cardboard. These were more detailed than the map.

The plan was for John and me to go in to the area the first ten days and then Jack would fly in and meet us at Trapline Lake. He would bring David and a second canoe, plus enough food for the four of us for an additional ten days. This was going to require some careful planning and since it was a lengthy trip and we had to carry everything over portages, we couldn’t take a lot of excess gear.

In addition to a tent and sleeping bags we would need cooking pots and utensils. I owned a cooking set of nesting pots, dishes and frying pans. We also bought a reflector oven made of aluminum that collapsed into a flat piece. Of course, an axe, fishing gear, dish soap and our personal items but few clothes. We had a serious first aid kit including suturing kit. We had seen it done when Doc Kelly sewed up Jack’s hand that had been cut with a power saw. I sure hoped I would not have to do that.

Food would be a critical item and with no refrigeration nothing like that would be possible. Nor could we take a lot of canned goods. Too heavy. We did find some freeze dried dinners that we could rely on but it was clear that most of our meals would be fish.

We did have a secret weapon. Really secret. We smuggled in a .22 Armalite rifle that disassembled and all the parts fit in the plastic stock. The whole thing was about a foot long or so and fit nicely into a rolled up sleeping bag. I thought we’d augment our fish diet with small game. What we discovered was that young ducks that could not quite fly were pretty easy to shoot from a quiet canoe. Mighty tasty grilled over a wood fire. The grouse were tame as chickens but the pine squirrels tasted horrible.

We made our own jerky, beef sliced in ¼” thick pieces about 2” wide and 7” long, rolled in a mix of salt, pepper and allspice and hung outside in the sun to dry.

I planned to make Bannock in the reflector oven. It was basically a baking powder biscuit that I made into two large loafs. Big fire with fireplace to direct heat and an eyeball for when baked. Carrying bread was impractical so flour instead.

The plan: I would make two sets of food packs, the first for John and me to take and a second set for Jack to pick up at the cabin.

With all this going on, poor Rip had been neglected. He had not learned how to hunt and would fly out of the trees toward you when you came out of the cabin. We’d throw him a few chunks of beef stew meat. Never gave much thought to what he would do after we left for 20 days.

John and I left on the train from St. Cloud, MN for the overnight to Winnipeg and were met there by one of the employees from the granite company. We went to the plant and picked up the canoe, and he then drove us to the drop off point at Rainier Lake.

This probably seems crazy today in the era of helicoptering parenting. Here we were a 19 year old and a 13 year old heading out into what was pretty much uninhabited territory with no radio or phone to contact anyone if something bad happened to one of us. It would take days for us to get back to the mining road where were scheduled to be picked up in 20 days! We had no idea how much traffic was going up and down that dirt track, if ever. But we were young and never considered the possibility of tragedy.

So we pushed off and started paddling. We had several lakes to get trough to get to Trapline and a number of portages, one almost a mile long. There is some debate about the sequence of lakes but it appears it was Coleman and Bain before we got the long paddle up Wilson and Trapline. The portages required two trips for both of us to get all the gear across. I think it took us three or four days of serious paddling to get to the far end of Trapline where we set up our base camp on an island. As we traveled we’d find a breezy point on which to camp that would keep the mosquitos somewhat a bay. The black flies, much more nasty biters, die off after their swarms in the spring.

We stopped for lunch on sunny points and ate our thick beef jerky and split a loaf of bannock that we washed down with lake water. We made our way into Trapline Lake, a long and very large lake. Since we left the mining road we had seen no one and few, if any, signs of people previously camping anywhere we stopped.

At our perfect site on the island, we built a big fire pit with large flat rocks to direct the heat into the reflector oven, cut pine boughs to put under our sleeping bags, and built a latrine back in the woods well away from the camp.

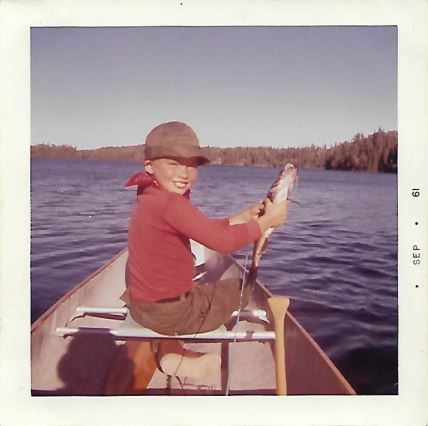

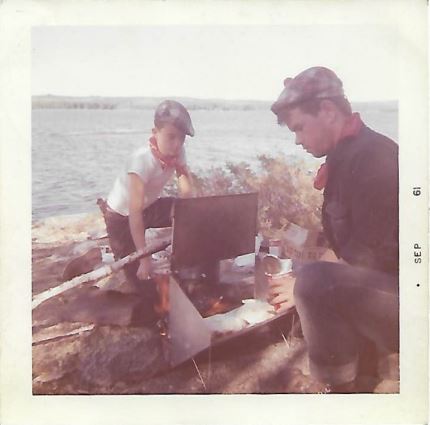

Fishing was stupid easy. In the morning we could catch two perfect pan sized walleyes that we’d bonk, filet, dip in corn meal and fry in bacon grease. The Crisco we used to bake the bannock and the slab bacon for frying we often ate the fish with a side of oatmeal or Ralston with sugar. No milk.

Trapline Lake is in Ontario so we’d crossed the border at some point and we had no fishing licenses for Ontario. Since we had not seen another human it did not seem worth worrying about.

From our base camp, John and I explored the lake. We had found that our aerial photos were much more useful than our maps. As we explored, we fished at one channel not far from our camp. We both hooked a walleye at the same time so we pulled up on a small island and started chucking our spoons out into the channel. In 45 minutes we caught 33 walleyes!

We also discovered an old, fallen-down, log trappers cabin on the opposite side of the channel. That was the only sign of human habitation we’d seen on the trip. We caught lots of northern pike and even baked one in the reflector oven. Bony but tasty. (We did not then know the technique for cutting out the pesky Y-bones.)

We noticed that there was a small lake that showed clearly on the aerial photo that was not on the map and wondered if the series of channels and small lakes would allow us to gain access to that lake. We decided to wait and do that when Jack and Dave flew in the next day.

Meanwhile, Jack headed out to the cottage to pick up the food packs for the remainder of the trip. As he got out of the car, Rip was trying to land on his head. Rip was unafraid of humans and depended on them for food. John and I had cleaned out the fridge before we left but had missed a couple of moldy hot dogs. Jack tossed the hot dogs out the door and sprinted for the car with the packs. We found out later that Rip had been sitting on the roof of the home of an elderly couple that lived a couple of hundred yards away. He would fly down when they were trying to leave and scared the shit out of them. We never confessed.

The Beaver float plane landed and deposited Jack, David, the canoe and all their gear at our camp on the island. Jack had thoughtfully added fresh steaks and a 12 pack of beer to the food list. We carefully knotted the necks of the bottles of beer to a line and lowered them off a rocky shelf. You only had to go down about 6’ to find really cold water, a fact we discovered while swimming. That night we had a feast of grilled steaks, baked potatoes and cold beer.

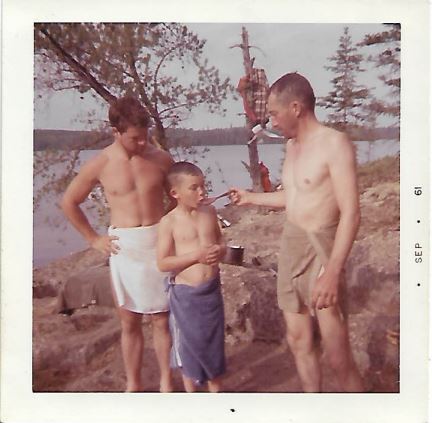

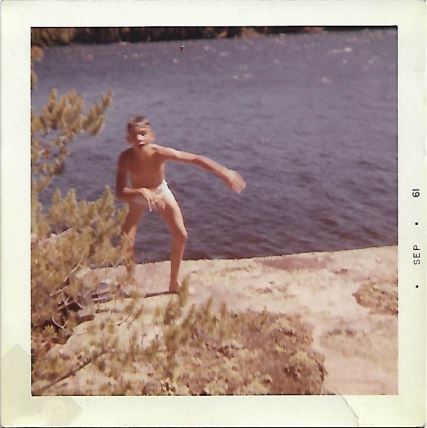

John and I had already discovered that a warm sunny day was good for a swim and for washing your clothes. As I said we did not carry a lot of clothes so we’d wash them in the lake, drape them over shrubs to dry while we took a swim and ate lunch.

The next day we headed up to locate out to see if we could find the mysterious lake that only showed on the aerial photo. As we paddled up the wide channel it would narrow and we’d find a beaver dam. We dragged the canoes around the dams and continued.

Finally, we came to a rocky hill at the end of a wide section of the channel. Although we could see a cut in the hill, we could not get to it because a reed bed blocked the end of the lake. Eventually we found a narrow channel through the reed bed, and after a short trip up a creek and a lift over a beaver dam, we paddled into the lake. As we sat there admiring the lake, we noticed a deer standing on the sunny hillside to our right. David flipped his spoon on a short cast and immediately hooked a nice walleye.

As we explored the lake, it seemed that no one had ever camped there for we could find no old campsites. The fishing was fantastic. David’s three biggest walleyes in one day weighed in at 18 lbs!

We named the lake Our Lake.

This lake was untouched and the fishing was amazing. We never did go deep for lake trout because we only had spinning gear, and lakers at that time of year would be deep. One day, John and I snuck up on a huge black bear tearing into a rotten log. The wind was blowing hard and we pushed thru the reeds. A spoon clanked against the side of the canoe and when he stood up we realized we were way too close. You could see the flies buzzing around his head! Fortunately, he dropped down and took off up the hill, crashing thru the brush as he went. We had no bear problems with our food. They had not yet learned you could steal easy food from humans.

Another day, we saw a big bull moose standing in the lake eating lily pads. The sun was setting behind us casting a band of reflected light across the lake. We paddled right in that sunlight reflected off the water when he had his head down and sat still when he had his head up. Jack was looking through the Kodak camera and did not realize how close we were. He clicked the camera and could then see it. And he was 16 feet closer than I was in the stern! The moose bolted for the shore, lunging and swimming and as hard as we paddled, we would not catch up with him.

On this trip, my fish chowder was created.

First, in the big kettle I would fry up some thick strips of bacon.

Remove them and set aside.

Then in the bacon fat I would soften a chopped onion.

Add about a quart of water and toss in a couple of sectioned carrots and a couple of potatoes. Salt and pepper. (Now I use chopped garlic and soften with the onion.)

When the carrots and potatoes are soft add the chunks of fish, usually 1” squares. Stir in instant mashed potatoes to thicken.

Top your bowl of chowder with the crumbled bacon.

If we had left overs we would add some liquid, more fish and bits of leftover duck or grouse. We’d call that “Conglomeration Stew”.

The following year, immediately after my return from my sophomore year, all four of us headed back to Our Lake. I have no photos of that trip or any written journal. On that trip, John Sr., Jack’s father, flew in with Pat, Jack’s half brother. When they flew out ,the now-heavier Beaver had a hell of a time getting enough altitude to get out of there. He took several runs at it before he could clear the ridge at the end of the lake. Scary.

In 1963, for a change of pace, we took a different trip to a place recommended by Doc Selznick. We called it derisively “Selznick’s Wilderness”. It was far from it. At one point we found ourselves paddling next to a busy paved highway. I seem to remember that Pat was on that trip and maybe Clint Elston?

One note on Rip the hawk. Early on, I had taught him to respond to my shrill whistle. I did not know if he survived the winter. After we returned from the canoe trip, I went outside the cabin and gave a whistle. He screeched in return and I could see him flying around in the trees but he did not come down. I was glad he survived.

Thanks for all the great adventures, Jack!